Best Age to Run a Marathon: What Age Is Ideal?

Oct, 9 2025

Oct, 9 2025

Marathon Age Suitability Checker

Your Marathon Suitability Report

20-35

Peak physiological performance

35-45

Strong aerobic base

45-55

Experience & endurance

55+

Mental resilience

When people ask marathon is a 42.195‑kilometre (26.2‑mile) road race that tests endurance, strategy, and mental toughness, the answer often hinges on age. Is there a "magic number" that guarantees a smooth finish, or does the ideal age depend on individual factors? Below you’ll find the science, the practical tweaks, and a quick self‑check to help you decide if you’re in the sweet spot.

Quick Takeaways

- Physiologically, the 20‑35 age window offers peak aerobic capacity and faster recovery.

- Runners aged 35‑45 still perform well if they focus on strength and injury prevention.

- People over 45 can finish a marathon safely, but must tailor volume, prioritize recovery, and monitor joint health.

- Training intensity, lifestyle, and medical clearance matter more than calendar age alone.

- Use the checklist at the end to see if your current health and schedule match your target age group.

Understanding the Physical Demands

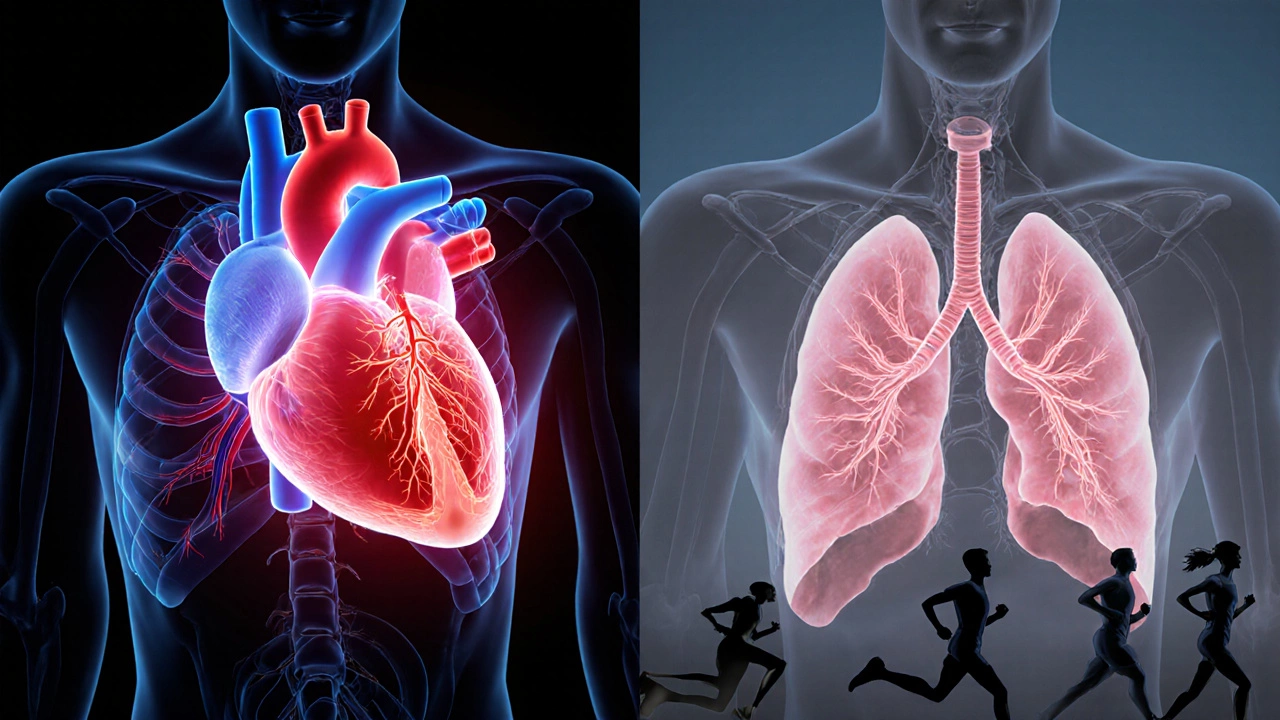

Running a marathon taxes the cardiovascular system - the heart, blood vessels, and lungs that deliver oxygen to working muscles for hours on end. Two key metrics often pop up in studies:

- VO2 max - the maximum amount of oxygen the body can use per minute. It peaks in the early 20s and slowly declines after 30.

- Recovery time - how quickly heart rate and lactate levels return to baseline after a hard effort.

Both metrics are influenced by age, genetics, and training history, but they can be improved or mitigated with the right plan.

Age‑Related Physiological Changes

As you add years, several body systems shift:

- Cardiovascular efficiencydeclines about 1% per year after the early 30s, meaning your heart pumps slightly less blood per beat.

- VO2 maxdrops roughly 5‑10% per decade if training volume drops. Consistent high‑intensity work can blunt this loss.

- Bone densitypeaks in the late 20s and slowly declines, raising fracture risk in older runners.

- Muscle mass and tendon elasticity decrease, which can affect stride efficiency and increase injury riskespecially in the knees, hips, and lower back.

- Recovery time lengthens, so a 70‑year‑old may need 48‑72 hours after a long run, versus 24‑36 hours for a 25‑year‑old.

These trends are averages; individual variation is huge. That’s why a personalized training planthat accounts for age, injury history, and lifestyle is essential.

Ideal Age Windows

Below is a pragmatic breakdown, not a hard rule.

| Age Range | Physiological Edge | Training Focus | Typical Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20‑35 | Peak VO2 max, fastest recovery, high muscle elasticity | Higher mileage, speed work, moderate strength | Overtraining, stress fractures if volume spikes |

| 35‑45 | Still strong aerobic base, mature mental toughness | Balanced mileage, added strength, more recovery days | Joint wear, slower healing of minor injuries |

| 45‑55 | Experience, efficient pacing, good endurance if trained | Reduced volume, focus on cross‑training, flexibility work | Bone density loss, cardiovascular strain, longer recovery time |

| 55+ | High mental resilience, disciplined pacing | Low‑impact cardio, strength maintenance, medical clearance | Higher injury risk, heart conditions, need for regular health checks |

Training Adjustments by Age

Regardless of where you fall, a few universal tweaks help keep you on track:

- Volume control: Older runners should cap weekly mileage at 70‑80% of what a younger runner would do at the same fitness level.

- Strength & mobility: Add two 30‑minute strength sessions weekly focusing on core, hips, and calves.

- Recovery protocols: Incorporate foam rolling, contrast showers, and at least one full rest day after any run longer than 15km.

- Intensity cycling: Replace some high‑speed intervals with tempo runs (80‑85% max HR) to preserve VO2 max without overloading joints.

- Nutrition tweaks: Increase protein intake to 1.2‑1.5g/kg body weight and ensure calcium & vitaminD for bone health, especially after 40.

Applying these principles lets you stay competitive even as the calendar advances.

Injury Risks and Prevention

Every runner worries about getting sidelined. The most common marathon‑related injuries are:

- Patellofemoral pain syndrome (runner’s knee)

- Achilles tendinopathy

- Shin splints (medial tibial stress syndrome)

- Stress fractures, especially in the metatarsals

Age amplifies these risks because connective tissue becomes less plastic. Mitigation strategies:

- Schedule a medical screeningevery 2‑3 years after 35 to check heart health and bone density.

- Use a gradual 10% weekly mileage increase rule - the classic “no more than 10%” keeps sudden overload at bay.

- Rotate shoe types every 400‑500km to manage impact forces.

- Prioritize eccentric calf work to protect the Achilles.

Mental & Lifestyle Factors

Running a marathon is as much a mental game as a physical one. Younger athletes often have more spare time but may lack the mental discipline that comes with life experience. Older runners may juggle family, career, and recovery, yet they bring a steadier mindset.

Key mental attributes that influence success across ages:

- Goal setting: Break the 42km into achievable milestones (5km, 10km, half‑marathon).

- Visualization: Picture race day logistics - start line, aid stations, finish line.

- Resilience: Accept that setbacks (missed workouts, minor aches) are normal; adjust, don’t quit.

When your schedule is tight, consider “run‑fit” workouts (3×1km at 5K pace with full recovery) that deliver mileage efficiency without eating up your week.

Decision Checklist: Am I in the Right Age Band?

- Do you have a clean bill of health (or a doctor’s okay) for endurance activity?

- Can you commit to 3-4 quality training sessions per week consistently for 16‑20 weeks?

- Are you comfortable with longer recovery periods (up to 72hours) if you’re over 45?

- Do you have a supportive environment - shoes, terrain, nutrition, and maybe a running group?

- Is your primary motivation realistic (personal challenge, charity, health benefit) rather than external pressure?

If you answered “yes” to most of these, the age you’re in is likely fine. If you’re unsure, consult a sports‑medicine professional and consider a shorter distance first.

Bottom Line

There isn’t a single best age to run a marathon that works for everyone. The data points to 20‑35 as the physiological sweet spot, but runners in their 40s, 50s, and even 60s regularly cross the finish line with proper preparation. The real key is matching training volume, recovery strategies, and medical oversight to the age‑related changes your body experiences.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a beginner start training for a marathon at any age?

Yes, beginners can train at any age, but the program must be adjusted. Younger beginners can handle higher mileage faster, while older beginners should start with shorter runs, add more cross‑training, and emphasize recovery.

How much does VO2 max really matter for marathon performance?

VO2 max sets the ceiling for aerobic capacity, but efficiency, lactate threshold, and running economy often determine race time. A runner with a slightly lower VO2 max but excellent efficiency can beat a higher‑VO2 max runner who is less economical.

Is it safe for someone over 60 to run a marathon?

Safety hinges on medical clearance, existing heart health, and a well‑structured plan that limits high‑impact miles. Many runners over 60 finish marathons by focusing on low‑impact cross‑training, strength work, and thorough recovery.

What’s the best weekly mileage for a 40‑year‑old aiming for a first marathon?

A typical range is 35‑45km per week, split into 3‑4 runs. Include one long run that peaks at 30km about three weeks before race day, two moderate runs (8‑10km), and one easy recovery run (5‑6km).

How can I reduce injury risk as I get older?

Prioritize strength training, maintain flexibility, follow the 10% rule for mileage increases, use proper footwear, and schedule regular check‑ups for bone density and heart health. Listening to early warning signs (persistent soreness, swelling) and backing off before they become serious is crucial.