Why Was Rugby Banned in France? The Hidden History Behind the Ban

Feb, 2 2026

Feb, 2 2026

Rugby Ban Impact Calculator

The 1931 rugby ban in France wasn't about violence—it was a political decision that shaped sports culture. This calculator models how the ban affected rugby's growth compared to football.

Key historical data:

- 1931: Rugby clubs < 300 | Football clubs > 1,200

- 1935: Football had nearly 2x more registered players

- 1936: Ban lifted but rugby never recovered its momentum

Enter years and click "Calculate Impact" to see results.

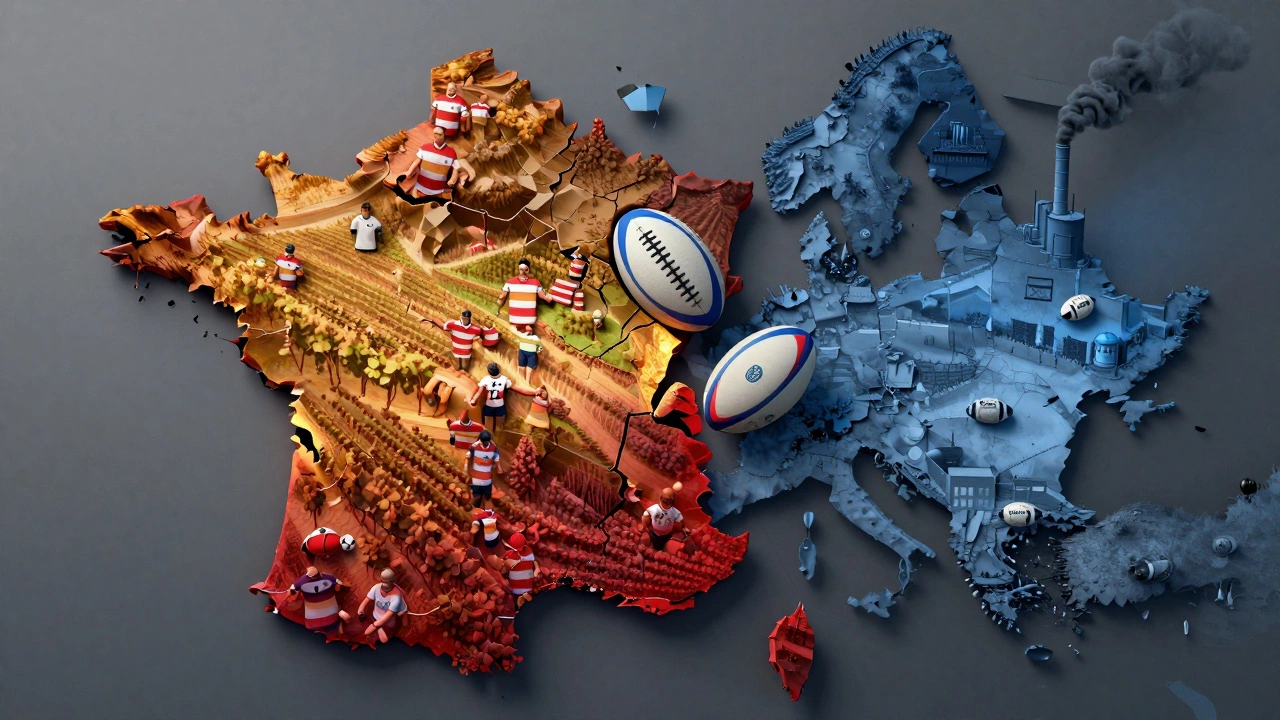

On a cold November day in 1931, French rugby players walked off the field not because they lost, but because they were told they couldn’t play anymore. The French government had just banned rugby union across the country. Not because it was too violent, not because fans were rioting, and not because the sport was unpopular. It was banned because it was seen as too British.

The Rise of Rugby in France

Rugby didn’t start in France. It arrived in the 1870s through British sailors, merchants, and engineers working in ports like Bordeaux and Marseille. French students who studied in England brought the game back to universities-especially in the southwest, where towns like Toulouse and Bayonne became early hotspots. By the 1890s, clubs were forming fast. The French Rugby Federation was founded in 1919, just after World War I, and the national team was already beating England and Wales regularly by the late 1920s.

But rugby wasn’t just a game. It became a symbol. In rural areas, it was tied to local identity. In cities, it was embraced by the middle class. Players wore wool jerseys, played on muddy fields, and celebrated with local wine. The sport had deep roots in the Pyrenees and the Basque Country, where it was seen as tough, honest, and French-even though it came from across the Channel.

The Political Divide

France in the 1920s and 30s was split. On one side were the republicans, the secularists, the anti-clericals. On the other were the conservatives, the monarchists, and the Catholic traditionalists. Rugby became a battleground. The sport was popular in the south, where the Catholic Church had strong influence. It was less popular in the north, where socialism and labor unions were rising.

The French government, led by the Radical-Socialist Party, saw rugby as a tool of the right. Clubs were often run by priests or local landowners. Matches were held on Sundays, the traditional day of rest for Catholics. Players wore uniforms that looked like military gear. The sport’s discipline, hierarchy, and emphasis on honor felt more like a relic of the old aristocracy than a modern national pastime.

Meanwhile, football (soccer) was growing fast. It was cheaper to play, didn’t require as much land, and was promoted by socialist groups as a working-class game. The French Football Federation was growing faster than rugby’s. By 1930, football had nearly twice as many registered players.

The Ban of 1931

The ban didn’t come out of nowhere. In 1930, a violent match between a French team and a British touring side ended with a player hospitalized. The press blamed rugby’s brutality. But the real trigger came from within the government. In November 1931, the Minister of Public Instruction, Alfred Masséa staunch secularist and anti-clerical politician who served as France’s Minister of Public Instruction in the early 1930s, issued a decree banning all rugby union activities in public schools and state-funded institutions. The official reason? "The game promotes physical aggression incompatible with republican values."

The ban didn’t outlaw rugby outright. It didn’t shut down clubs. But it cut off its lifeline: schools, youth programs, and public funding. Without access to gyms, fields, or teachers, rugby’s growth stalled. Clubs survived in private hands, mostly in the southwest, but the sport lost its chance to become mainstream.

Football, on the other hand, got state support. It was taught in schools. It was played in public parks. It was promoted as the "people’s game." By 1935, France had over 1,200 football clubs. Rugby had fewer than 300.

The Aftermath

The ban lasted just five years. In 1936, when the left-wing Popular Front came to power, the ban was quietly lifted. But the damage was done. A generation of French boys had grown up playing football instead of rugby. The cultural momentum had shifted.

Rugby didn’t disappear. It survived in pockets-Toulouse, Perpignan, Biarritz, and the Basque region. But it never regained the national presence it might have had. Today, France has one of the strongest rugby teams in the world, and the Six Nations is a major event. But rugby remains a regional sport in many ways. The north still barely watches it. The south still lives for it.

Why It Matters Today

The ban of 1931 wasn’t about safety. It wasn’t even about the sport itself. It was about control. It was about who got to define French identity. The government didn’t want a game tied to religion, tradition, and regional pride. They wanted a unified, secular, modern nation-and football fit that vision better.

That’s why, today, if you walk into a school in Lyon or Lille, you’ll see kids playing football. If you go to Toulouse, you’ll see kids in rugby jerseys. The same country. Two different sports. One ban. A century of consequences.

The Legacy of the Ban

France’s rugby teams still win. They’ve won the Six Nations multiple times. They’ve beaten New Zealand. But they’ve never had the same cultural grip as football. The national team doesn’t fill stadiums the way the football team does. Youth programs are underfunded outside the southwest. Parents still choose football because it’s safer, cheaper, and more widely accepted.

The ban of 1931 didn’t kill rugby. But it stopped it from becoming the national sport. And that decision echoes today. When France hosts the Rugby World Cup in 2027, the stadiums will be full-but mostly in the south. The rest of the country will watch from afar.

What Could Have Been

Imagine if the ban never happened. What if rugby had been taught in every French school? What if it had become the sport of the republic, not just the south? France might have had a deeper talent pool. It might have challenged New Zealand and South Africa more consistently. It might have changed how the world sees the game.

But history doesn’t run on "what ifs." It runs on decisions made by politicians who feared tradition, distrusted religion, and wanted to build a new France-even if it meant burying a game that had already found its soul.

Was rugby banned because it was too violent?

No, the official reason cited was that rugby promoted "physical aggression incompatible with republican values," but violence wasn’t the real issue. Other contact sports like boxing and wrestling weren’t banned. The real reason was political: rugby was seen as a tool of conservative, Catholic, and regional elites, while football was promoted as the secular, modern, working-class alternative.

Did the ban affect French rugby’s success today?

Yes, indirectly. The ban in 1931 cut off rugby’s access to schools and public funding for five years. That meant a generation of French children grew up playing football instead. As a result, rugby never became a nationwide sport. Today, France has a strong national team, but its grassroots base is still concentrated in the southwest. Football remains the dominant sport in most regions, limiting the talent pool and funding for rugby outside its traditional heartlands.

Why did football become more popular than rugby in France?

Football was cheaper, easier to play on small fields, and promoted by socialist and secular groups as the "people’s game." It didn’t require expensive equipment or large grounds. More importantly, the French government actively supported football in schools and public parks after 1931, while rugby lost state backing. By 1935, football had twice as many registered players as rugby.

When was the rugby ban lifted?

The ban was lifted in 1936, after the left-wing Popular Front came to power. The new government reversed the policy, allowing rugby to return to schools and public institutions. But by then, the damage was done. Football had already taken root as the dominant sport, and rugby never recovered its lost momentum.

Is rugby still regional in France today?

Yes. Rugby remains strongest in the southwest-Toulouse, Bayonne, Perpignan, and the Basque Country. These areas have deep cultural ties to the sport, and local pride still revolves around rugby clubs. In northern and eastern France, football dominates. Even today, many French people outside the southwest rarely watch rugby unless it’s the Six Nations or World Cup.

Final Thoughts

France didn’t ban rugby because it was dangerous. It banned it because it was different. And in the end, that difference cost the sport its chance to become something bigger. The game survived, but not as the national symbol it could have been. Today, when you watch France play rugby, you’re watching a sport that refused to die-even when the country tried to make it disappear.